"The Real Housewives of Atlanta" exist in the murkiness of accountability work.

RHOA gives viewers a beautifully nuanced depiction of how, as Kai Cheng Thom writes, we “collectively resist the culture of disposability."

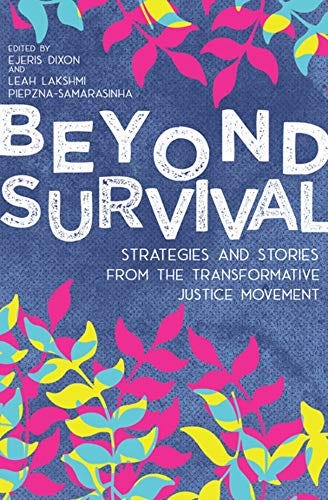

In the essay “What to Do When You’ve Been Abusive,” Kai Cheng Thom writes about the complexities of abuse and intimate partner violence, particularly the reality that victims and survivors can also be capable of causing harm. Her essay, first published in 2016 and later in the 2020 book Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement, describes the nuances of working with survivors and abusers and offers nine steps to help her readers address how we have been harmed and/or harmed others.

Thom’s work is rooted in her own life experience as a Chinese Canadian, non-binary trans woman, and it is profoundly spiritual and rooted in transformative justice. She is an activist, somatic coach, intimacy educator, psychotherapist, spiritual healer, conflict mediator, and the author of four books: from the stars in the sky to the fish in the sea, a picture book that tells the story of Miu Lan, a child who can take any form they want; Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars: A Dangerous Trans Girl’s Confabulous Memoir; the poetry book, a place called No Homeland; and I Hope We Choose Love: A Tran Girl’s Notes from the End of the World. In August, Penguin Random House will publish her newest book, Falling Back in Love with Being Human: Letters to Lost Souls, a collection of letters the author described as “prayers or spells or poems” meant “to affirm the outcasts and runaways she calls her kin.”

I first read Thom’s essay when I started watching “The Real Housewives of Atlanta” last May. It was weeks after I—very publicly—quit my job, and I was thinking a lot about abusers, especially white ones. I thought about how they internalize white supremacy, patriarchy, and misogyny and how their understanding of self and allyship is predicated on the rejection of Black and Brown lived experiences. This is an allyship, built under empire, that tells them our grievances and suffering are decontextualized/disconnected anomalies removed from their whiteness.

Almost a year later, I don’t care about white accountability; my experiences in white media spaces have made me distrustful of most attempts. But I am still committed to understanding how these systems shape us all, and I want to think through and write about and uplift histories that invite us all to circumvent capitalism and empire. I want to think about how these systems have shaped how I understand myself and those around me, and how Black communities undermine empire—how we live, thrive, heal, and love. “The Real Housewives of Atlanta” gives viewers a beautifully nuanced depiction of how, as Thom writes, we “collectively resist the culture of disposability that says that people who have done harm are no longer people, that they are ‘trash,’ that they must be ‘canceled.’”

I am a late-bloomer “Real Housewives of Atlanta” fan. The series premiered almost 15 years ago, in October 2008, and its fifteenth season airs later this year. It follows the lives of women in Atlanta as they navigate different professional and personal challenges. The cast changes slightly every season. I started season ten earlier this week, and the peaches this season are NeNe Leakes, Shereé Whitfield, Kandi Burruss, Cynthia Bailey, Kenya Moore, and Porsha Williams.

Like all the Housewives in other cities, the women are privileged, and their material needs are met. They have homes that get bigger every season; they vacation; they eat and travel in and outside of Atlanta. They start different businesses and can spend time doing things that fulfill them. They also have moments when a housewife, a husband, a friend, or a relative is homophobic, like with season 9’s plotline around Kandi possibly being a lesbian. In his blog, “Reclaiming Anger, Codi Charles writes that as RHOA fans, we must “critically think about the ways these Black women capitalize off of queer folk, as they continue to leverage queerness as the worse thing one could be.”

I started watching the series last May. I was looking for something to binge, and my friend, Imani, who had already watched it in real-time, recommended it. It is the first to feature an African-American cast, and the show is set in a city rich with Black history and revolution.

Every season, the women of Atlanta also have profound moments that I refuse to believe Andy Cohen is responsible for.

Every season the women argue and harm each other. Sometimes these escalate into physical altercations, like when Shereé pulls Kim’s wig or when Cynthia kicks Porsha in the stomach. Much of the tension is scripted, sometimes hilariously so, like when Mama Joyce, Kandi’s mom, visits a lawyer to prove Phaedra is lying about divorcing Apollo and then tries to confront her or when Kenya Moore and Shereé exchange barb after barb over their unfinished houses.

Yet every season, the women of Atlanta also have profound moments that I refuse to believe Andy Cohen is responsible for, when you can tell one of them has gone over the unofficial line they have agreed off camera to never cross. The tears and fear and rage and betrayal are just too raw. (Imani tells me they become better actors in later seasons, and I agree. Multiple things are true.) They are better at crying on cue, and their confessionals—which have always been brilliant—are sharper. I started season ten’s “All White Never Forget Showdown.” I still don’t know if Kenya is actually married.

But in the show’s rawest, most authentic moments, when you can sometimes hear the women remind each other that the cameras—and all of us—are watching, these women are transformed. They immediately and collectively step in to mediate when something goes too far. They separate the persons arguing or fighting, and then they all split into their respective cliques and process and debrief. The cameras pan in and out of different perspectives and witness accounts. The next day or next episode, someone will suggest the women gather for lunch or dinner. In these spaces, they air their grievances and exchange apologies. Sometimes most of the group agrees on who has harmed who; other times, the group is divided. Sometimes the group is divided and then united after a specific truth is revealed, like in the season nine reunion. After watching Kandi and Phaedra, who have been friends for years, grow apart all season while rumors escalated, Porsha admitted that Phaedra was the one who told her that Kandi and her husband Todd tried to drug and rape her. Kandi is devastated. Porsha is panicked. Phaedra is nearly speechless. It is truly one of the best TV moments I have watched.

It’s not always easy to watch these moments, though. Sometimes I take breaks between specific episodes or seasons that are incredibly explosive, like when NeNe and her husband Greg argue with Peter, Cynthia’s husband, or when Brandon, Kenya’s friend, fights Apollo, Phaedra’s husband. Most of the fights are verbal, and these often go too far. It’s not easy to watch the fear or shame the women feel after causing each other harm.

In her Beyond Survival essay, Thom invites readers to step into this discomfort. She provides readers with steps to use when someone has been harmed, including beginning with listening to the person who is hurt. The harmer is then called to acknowledge their harm, including the understanding that while there are reasons, context, and history behind harming, these factors are not excuses. “It’s easier for privileged individuals to abuse others because of the extra power social privilege gives them, but anyone is capable of abusing anyone,” Thom writes, inviting those who harm to resist “comparing or trivializing” the experiences of survivors and abusers.

“The Real Housewives of Atlanta” exist in the murkiness of accountability work. They call each other in, choosing time after time to hold space for each other’s experiences and pains and joys. I love seeing Kenya and Shereé empower each other as domestic violence survivors; how Cynthia stands up for herself; how they all support each other through health scares and divorces; and how they celebrate each other and themselves. They show that surviving and healing and accountability work is messy and all of it requires love and community.