I talked to Ramona Hernández, director of the only US university-based institute exclusively studying Dominicans.

In early April, I spoke with sociologist Dr. Ramona Hernández, the director of the City University of New York’s Dominican Studies Institute, a position she has held for the last 22 years.

The Dominican Studies Institute is the only U.S.-based academic higher educational space focused exclusively on studying Dominican life and migration worldwide. The institute houses the Dominican Library, curated by chief librarian Dr. Sarah Aponte. DSI researchers discovered Juan Rodriguez, the first Dominican to live in New York City, who settled here in 1613. They uncovered the stories of hundreds of Dominican veterans from World War II, including Esteban Hotesse, and institute exhibits include “Hispaniola: One Island, Two Cultures”; “The Evolution of an Ethnic Community: Dominican-Americans in Upper Manhattan”; “Dominican Rock: An Audiovisual Experience”; “The Artistry of Dominican Carnival: A Multimedia Exhibition”; and “Sixteenth-Century La Espanola: Glimpses of the First Blacks in the Early Colonial Americas.”

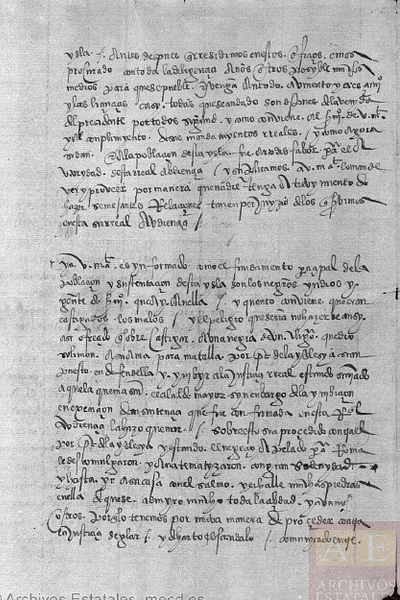

DSI created the “First Blacks in the Americas: The African Presence in the Dominican Republic,” a bilingual digital resource centered on the history and timeline of the first Africans brought to the Dominican Republic. This research describes Black resistance against colonizers, especially against gender-based violence by Spanish colonizers in the 16th century. The website includes manuscripts and records on the first African women on the island, including unnamed Black women who cooked and cleaned and organized behind resistance efforts and enslaved Black women who poisoned enslavers on sugar plantations.

Ramona works with historians, scholars, researchers, students, and community members. Her research and tenure focus on “recognizing the contributions of the Dominican people to fight and try to undermine the evil of society,” she described when we talked over Zoom.

She was born in La Romana and arrived in the Bronx in 1973 with her family. She lived in a neighborhood home to mostly Puerto Ricans and African Americans. Her family, which included nine or ten other relatives, including her parents, lived in a two-bedroom apartment. She could not sleep as a child, and she studied often at night in the kitchen.

Ramona constantly observed the material conditions of her family’s world, the conditions in the Bronx, and the things Black immigrant people must do to survive under empire. She observed how her parents supported her family in the United States while sending whatever clothes or money they could back to the island. The sociologist described the influence of women like her mother and grandmother, intense, violent, and formidable women—“mujeres con machetes”—whose existence and lives were constantly resisting the violent machismo of the Dominican Republic. Her family life and immigration journey inform how she approaches sociological and historical work. “Seeing the reality of what we were led to what I am. Somebody who sees a hard-working community, who does anything that needs to be done to provide a better life for self and their family, which in our case is an extended family,” she said.

She studied Puerto Rico as an undergrad at Lehman College; Latin American Studies at New York University; and Caribbean Studies at The Graduate Center, CUNY. Her commitment to writing about Dominicans happened repeatedly she told me. She was often asked to focus on the Latino experience throughout Latin America in the academic spaces she found herself in, but she refused, choosing instead to focus exclusively on writing and speaking and studying the socio-economic conditions behind our migration.

Ramona’s bibliography includes 1998’s The Dominican Americans, 2002’s The Mobility of Workers Under Advanced Capitalism: Dominican Migration to the United States, and 2004’s Desde la Orilla: hacia una nacionalidad sin desalojos.

Since her first book’s publication 25 years ago, Ramona and the DSI have also published reports that focus on the socio-economic status of Dominicans and how COVID has impacted our communities. Her research especially highlights the perspectives of Dominican women and the socio-economic reality we find when we leave the Dominican Republic.

***

I was introduced to Ramona and her work when I first read The Dominican Americans, which she co-published with professor and the first DSI director Silvio Torres-Saillant. The book is written with general readers and students in mind and offers a succinct, clear, and accessible way to engage with and analyze Dominican history. The authors intentionally describe our collective stories and narratives with Haiti, highlighting how the U.S. instigated and continues to instigate violent conflict between Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The book also describes the gender-based violence against Black and Taino women on the island, from the rapes following Columbus’s arrival to the USA’s involvement in President Joaquín Balaguer’s sterilization efforts.

I spoke with the sociologist just after the publication of DSI’s latest report, “Quisqueya in Borinquen: A Socio-economic Profile of the Dominican Population in Puerto Rico,” which studies our labor force participation, education, income levels, and population dynamics.

Dominicans have migrated to Puerto Rico for decades, making us the largest immigrant and ethnic group on the island. As of 2021, over 58,000 of us live in P.R. Almost 60% of these citizens identify as female, and according to the 52-page report, which uses data from the U.S. Census, these numbers are an underestimate.

From “Quisqueya”:

Although the number of Dominicans not counted by the Bureau of the Census is not known, according to the analysis by Duany (1992) the percentage of Dominicans who do not fill out Census forms relative to those who do is 37%. If one applies this figure to the Dominican population in 2021, which was 58,352 according to the U.S. Bureau of the Census, one arrives at an estimate of 21,590 for the Dominicans who were not counted by the official statistics. If this figure is added to the official Census estimate, the sum is equal to 79,942 Dominicans residing on the island in 2021.

The report lists the various social, natural, and political disasters, from earthquakes to hurricanes to U.S. settler colonialist policy, that have devastated Puerto Rico in the 21st century and the impact these have on Dominicans. “Quisqueya in Borinquen” states that between 2016 and 2020, Dominicans under 17 faced high poverty rates, at “75.9%, compared to 57.2% among the Island’s population overall.” The report states that if these rates are “not reversed, the high poverty among children and youth will have a devastating effect on the health, development, and well-being of the Dominican population.”

Ramona described how we are often ignored or erased from reports or studies about P.R. despite the island having the seventh-largest U.S. Dominican population, and we are a small and essential part of the country’s labor force. From “Quisqueya in Borinquen”: “Dominicans have substantially higher labor force participation rates than the overall population in Puerto Rico. On average, for the period of 2016 to 2020, the participation rate for Dominicans was 63.6% while it was only 44.3% for Puerto Rico overall.”

The material conditions Dominicans, particularly children, and women, find in Puerto Rico are not an anomaly to that country. DSI’s research demonstrates that we see these conditions in other countries and cities we migrate into, including New York City, home to the largest U.S. Dominican population.

***

I wanted to talk to Ramona for the 25th anniversary of The Dominican Americans, a book helping me understand the nuances of our displacement and how the rupture from our native lands intersects with every aspect of our lives as Dominicans.

I am learning to understand and write why our journeys and stories about leaving the island are so similar; why we encounter the same material conditions and socio-economic struggles no matter where we migrate. Living and learning under empire means unlearning what we know about ourselves and our stories and histories—how we have always resisted colonialism, empire.

“Whenever you have oppression, you have resistance. This is automatic. This is a dialectical process,” Ramona added.

Ramona and I discussed how violence against us has existed since the first day of European colonialism, since the first and ongoing moment of displacement, from the first genocide to foreign involvement and dictatorships. Our rebellion against oppressors has existed since day one, despite empires wanting us to believe otherwise. She cited how, under Trujillo and Balaguer, students were in daily, violent revolt against the state, and how the state killed and disappeared them daily.

And in the introduction to The Dominican Americans, Ramona and Torres-Saillant describe one of the first revolts after Columbus’ arrival to Ayiti in 1492. He encountered Tainos on the island and set up settlements with soldiers before sailing back to Spain to inform the crown of what he found: “The Spaniards built there their first fort, called La Navidad, prior to the full colonization process. The thirty-nine Spanish soldiers who staffed the fort perished at the hands of Taino warriors, in retaliation for a rampage of rape and abuse of Taino women perpetuated by the Spaniards during the admiral’s absence.”

Since the first day of colonial violence, we have resisted.

“Whenever you have oppression, you have resistance. This is automatic. This is a dialectical process,” Ramona added.

***

I love reading and writing about our resistance history and learning from other Dominican women who teach and embody the revolutionary spirit of Ayiti.

The Dominican Republic and Haiti are countries of armed revolution.

Our island began the Americas, our ports were the first stop on the slave trade into the region. We are home to the first plantation, the first church—the first resistance. So much resistance work has always happened and is currently happening in the Dominican Republic, New York City, Puerto Rico, and everywhere Dominicans exist and build and love.

What does it mean to sit with this history?

How do we create and uplift international Dominican stories and histories of struggle and resistance?

As far as I can tell, the history both of specific parts of the Caribbean and of the region as a whole unknown to the majority of the US. Even though the history of the Caribbean is essential to understanding the development of the Americas. As someone descended from people in Jamaica, St. Lucia, and Panama, I’m always glad to learn more about the specific history of the places and resistance to oppression that has never ended there.