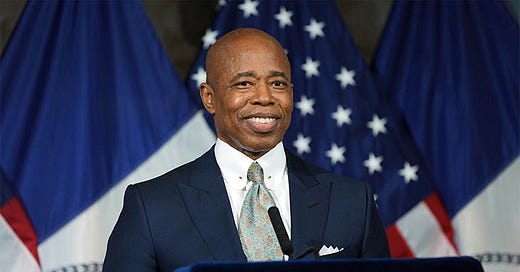

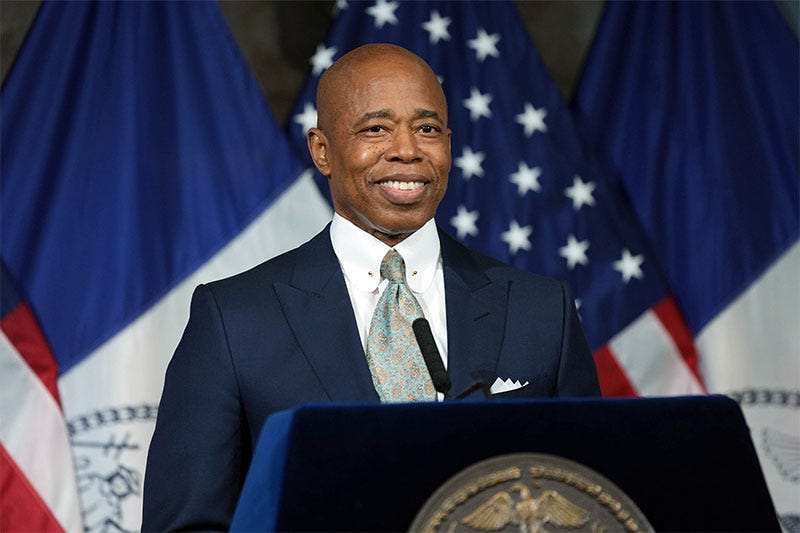

Eric Adams, mayoral power, and the $102.7 billion NYC budget.

Understanding mayoral power means analyzing the city budget—an almost impossible task.

In January, Mayor Eric Adams released his preliminary city budget for the 2024 fiscal year.

Last month I wrote about Adams' first year in office and mayoral power.

Understanding mayoral power means analyzing the city's $102.7 billion budget and how Adams wants to spend it, yet neither is easy or intuitive.

The city budget, which includes revenue from our city tax dollars, funds whatever organization, department, or project the mayor considers a priority, which can be anything from policing and fire training to schools and parks to housing and office developments and senior homes. The city budget consists of, according to New York City's Independent Budget Office, estimates for revenue, expenses, and the capital budget.

The preliminary expense budget funds all of the city government's day-to-day operations, from the salaries of government employees to office supplies to debt services. The preliminary capital budget is separate and dedicated to the city's land and infrastructure "used either in support of government operations (such as government offices, schools, and fire stations) or for general public use (such as roads, bridges, libraries, and parks)."

Adams described his financial priorities—"public safety, affordable housing, and clean streets"—and where he planned to make cuts to save New York City money. He requested that various city agencies "self-fund new needs with preexisting resources." Katie Honan of The City reported that the mayor justified cuts, like the proposed $36.2 million to the New York Public Library, due to "the city's current economic challenges, from the cost of settling multiple expired labor contracts to this year's $1 billion price tag to address the bused-in migrant crisis."

Along with publicly presenting the budget, the Mayor's Office of Management and Budget published 17 documents, available as "January 2023 Financial Plan, Fiscal Years 2023 - 2027." These include a 242-page financial plan, a 530-page expense and revenue report, a 143-page preliminary capital budget, and a 1,340-page register of every community board request across the five boroughs.

The city budget documents, including supplemental materials, total more than 15,000 pages.

I spent hours this week going through these, spending the most time with the summary, financial plan, and preliminary capital budget. I wanted to see a breakdown of the billion-dollar budget in a way that makes sense to someone without an economy, political science, or business degree. I wanted to read how billions of dollars can address the housing and houselessness crises in the city, what housing and construction projects Adams and the City Council approve, and how housing funds and projects differ from borough to borough. Yet reading through the budget documents is not easy.

The city budget documents, including supplemental materials, total more than 15,000 pages.

The report's summary, a 35-page document that offers the easiest start to reading the budget, describes the state of the city and national economies, referring to the decline of the stock market and Wall Street profits. It also includes "support" for "funding to assist low-income prospective homeowners" and "expanding enforcement against tenant harassment"; efforts to address greenhouse gas emissions; and a 10-year infrastructure plan.

The 242-page financial plan offers a more detailed look into Adams' predictions for the city's costs and revenue over the next four years. Most of the city's income comes from taxes and federal and state aid. But mostly taxes. According to the mayor's forecast, the tax revenue will be $69,002,000,000 (2023), $68,888,000,000 (2024), and $70,618,000,000 (2025.)

In the capital budget, a separate report, he presented details of the city agencies that will receive funds because they have, as IBO describes, "construction, reconstruction, acquisition, or installation of a physical public improvement with a value of $35,000 or more and a 'useful life' of at least five years." These include the NYPL, the Department of Education, the police department, the Department of Correction, and Parks and Recreation. For 2024, Adams requested a total of $12,262,645,168. The three agencies receiving the most funds are the DOE ($2,824,872,015), "Resiliency, Technology & Equipment," a category under the Department of Citywide Administrative Services ($1,294,127,858), and the Department of Correction ($1,253,906,871).

These are many numbers, and comparing the numbers in each document is frustrating and time-consuming. I messaged several comrades with more expertise reading city budgets to ensure I didn't imagine how deliberately obscured the city’s finances are.

Despite OMB's proclaimed "pride in transparency," our city politicians do not want us to have the skills, knowledge, or time to investigate where they spend billions of dollars every year.

Along with the mayor, who else reviews and approves the city budget?

The City Council reviews Adams' preliminary report and holds public hearings, which inform the edited budget they return to the mayor.

There are 51 City Council members, and for the Bronx, they are Eric Dinowitz, Kevin C. Riley, Marjorie Velázquez, Pierina Ana Sanchez, Oswald Feliz, Althea Stevens, Rafael Salamanca, Jr., and Amanda Farías. The Council has different committees, including the Committee on Finance, which oversees the Department of Design and Construction, New York City's Banking Commission, the IBO, the Office of the Comptroller, and the Department of Finance.

This committee is also responsible for reviewing the city budget. There are 18 council members on this committee, including Velázquez, Sanchez, Stevens, and Farías. From March to April, the Council reviews the budget and hosts public hearings on Adams's proposals. Then, they present their analysis and concerns to the mayor, and in April, Adams presents them with his executive budget, which the Council and Borough Presidents review. If the city budget is approved by a majority Council vote, it is adopted and in effect by July 1, the start of the new fiscal year.

The Committee on Finance was scheduled to meet Friday, March 24, but the meeting was deferred.

Other news and culture from around New York City

Brooklyn-born poet, artist, and activist Aja Monet released her new single and short art film, "the devil you know.” In 2018, I interviewed Monet about her work and collection, My Mother Was A Freedom Fighter for Shondaland.

“City of Faith: Religion, Activism, and Urban Space” is an exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York that centers on “South Asian American and other communities who have faced religious profiling and surveillance—particularly after 9/11.” The exhibition will be on display through October 22, 2023.

Workers at Trader Joe’s at a Lower East side location in Manhattan filed their petition to unionize on March 22. They are the fourth Trader Joe’s store to unionize this year.

For World Doula Week, please follow and support the work of Bx (Re)Birth and Progress, “A collective of Black mamas & Birth workers invoking self-determination through mutual aid, community doula services, and weekly conversations.”