A night at the Bronx County Historical Society celebrates Malcolm X and Yuri Kochiyama

The celebration featured the exhibit, “With Our Hands/Con Nuestras Manos," which debuted on April 22 and features art by Bibi Esperanza Martell and Mariposa Fernández.

On Friday, May 19, I walked to Bainbridge Avenue with my friends Siddika and Danielle. We visited the Bronx County Historical Society, a nonprofit founded in 1955 for the “preservation, documentation, and public interpretation of the history of The Bronx and lower Westchester County from its earliest human habitation by indigenous Americans through the present.”

All three of us are from the Bronx, and it was Siddika’s and Danielle’s first time at the Society. I vaguely remember visiting either this building or the Edgar Allan Poe Cottage as a student at St. Philip Neri. I don’t remember anything I learned on school trips, and it’s been my friend Vani, a non-native to New York City who has lived and organized here, who actually introduced me to organizers, historians, and writers who are actively preserving and telling Black Bronx stories.

Several friends and comrades shared the flyer for the evening’s exhibit, “With Our Hands/Con Nuestras Manos.” It debuted on April 22 and was curated by artist and organizer Bibi Esperanza Martell and historian Steven Payne. The exhibit features the art of Esperanza and Mariposa Fernández, along with other archive items owned by the museum.

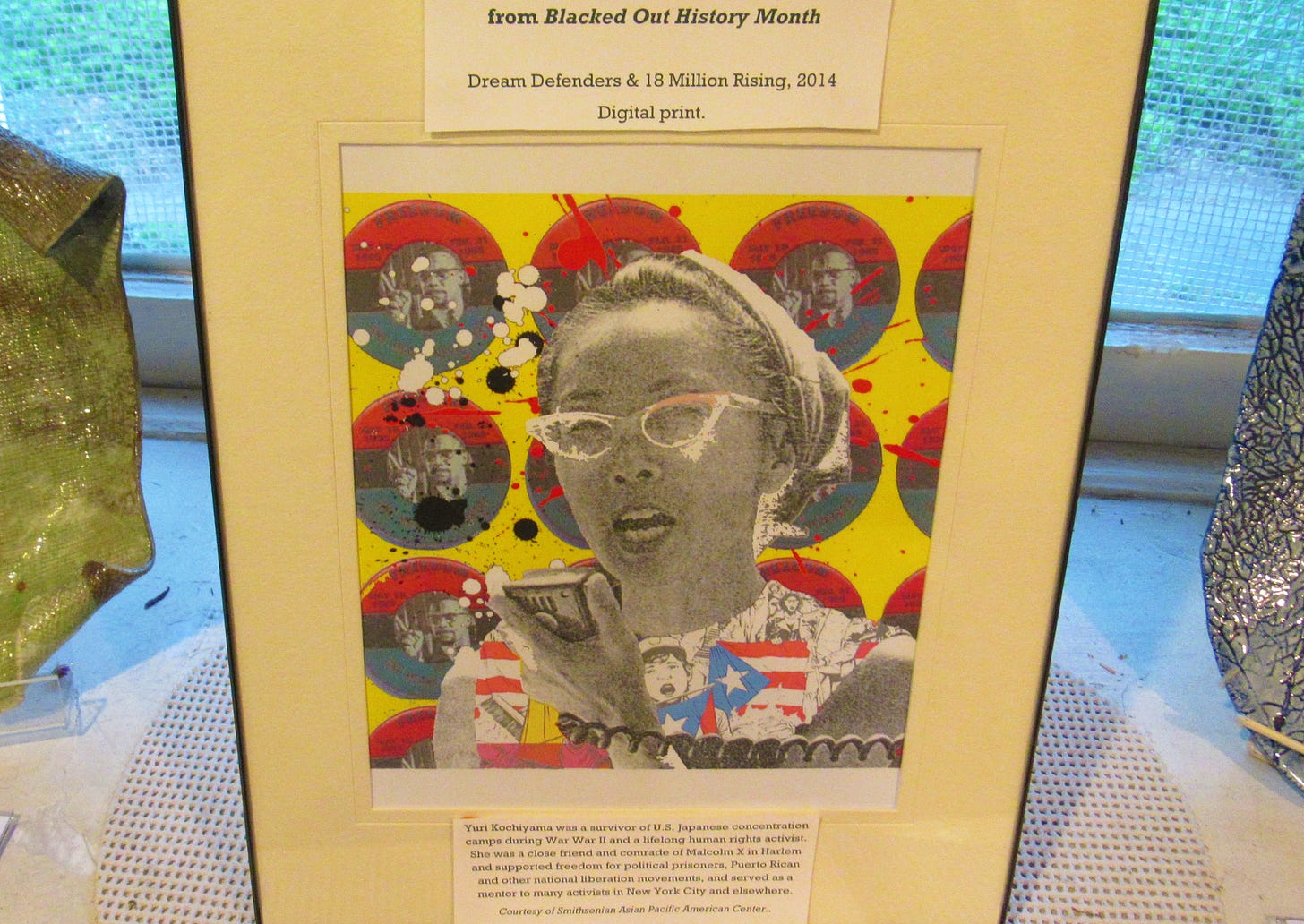

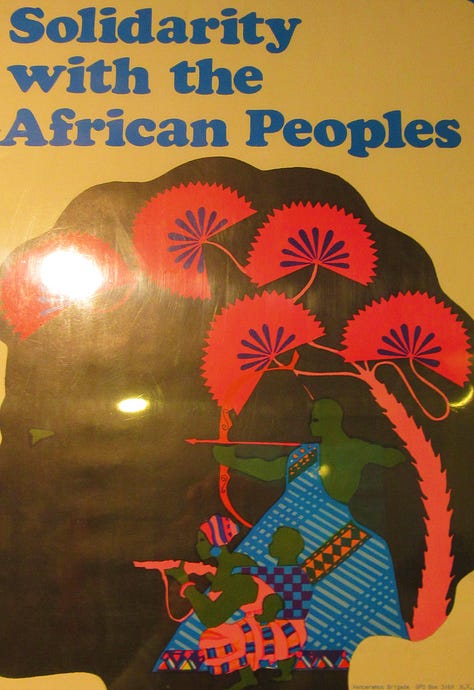

Yesterday’s program celebrated the birthdays of Hồ Chí Minh, Malcolm X, and Yuri Kochiyama, and the evening’s art and conversations highlighted the influence of these revolutionaries and other freedom fighters on NYC Puerto Rican artists and organizers.

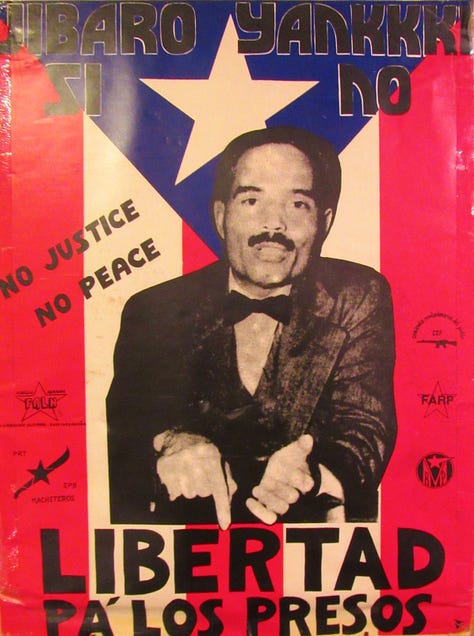

The program began towards the back of the small house. Esperanza started, sharing how the room we stood in featured, along with archive pieces from the BCHS and Mariposa’s art, items that were part of her private collection throughout her lifetime organizing and building in the Puerto Rican struggle, including her political posters and ceramic cemis she created to honor Taínos.

She was born in Puerto Rico, in Bayamón, and her parents were forced to migrate to New York in the 1950s. She has been a part of the struggle for Puerto Rican independence, has worked with political prisoners, and is one of the founders of the South Bronx-based healing space for women of color, Casa Atabex Aché.

After she described her posters and sculptures, Esperanza introduced Mariposa Fernández, a Bronx-born artist, educator, organizer, and poet.

I met Mariposa last summer when we both worked as instructors for a five-week writing program for Bronx high school students organized by Lehman College’s Jane Kehoe-Higgins. (I will write more about this teaching experience this summer.)

She discussed growing up in the Bronx and learning how to find her voice in drawing and painting. She discussed a painting she made during a sleepless night and the decision to incorporate her body into the art. The painting is red and vibrant, featuring a naked woman shackled at her hands and wrists. She is bleeding freely. The artist used menstrual blood to create this piece.

“That’s what it feels like when I create art—I feel like I am connected to something mystical,” Mariposa said.

Esperanza described Mariposa’s art as a way “to honor women beyond the pain, beyond oppression.”

For the second half of the evening, we moved into a room set up with about nine or ten rows, each with three chairs. Members of the community spread out and listened to Esperanza and Mariposa discuss the power of freedom fighters in their work, focusing on the life of Kochiyama and how it intersected with Malcolm’s.

Kochiyama was a Japanese-American political activist whose organizing was shaped by her and her family’s experience in U.S. internment camps in the early 1940s. She was born in California but moved to Harlem after her release from the camps.

Esperanza and Mariposa discussed how Kochiyama was mentored by Malcolm X, eventually becoming his secretary. They played a video of Kochiyama describing her first time meeting Malcolm in NYC and passed around the BCHS’ copy of Kochiyama’s 2004 memoir, Passing It On.

They each took turns discussing the role of Malcolm in Kochiyama’s life, in their lives, and the role of Kochiyama in their lives and art.

Esperanza shared how she met and knew Yuri, describing their time together as “a small moment part of a powerful and profound life,” and Mariposa shared how she and her students studied Malcolm’s writing and speeches. She invited one of her students to describe his first time reading the revolutionary’s autobiography at 13 versus his experience reading it again at 26.

It was an evening rooted in Black, Bronx, Caribbean, New York City resistance, and both women reminded the audience of the power of building in our communities, “by any and all means necessary,” especially as younger Bronx organizers.

The exhibit is open until August 6.