A Brooklyn ball honors O’Shae Sibley

The 28-year-old was fatally stabbed on July 29 for voguing at a gas station.

On Friday August 4, a memorial ball and vigil was held to honor O’Shae Sibley.

The 28-year-old dancer and choreographer was stabbed and killed on July 29 because they were queer, Black, and voguing to Beyoncé.

The killer, currently in police custody, is 17 years old.

The memorial was organized to honor Sibley’s life and to call attention to the violence Black queer and transgender women, men, and children face in New York City and across the country.

Speakers reminded the people supporting—and the various white photographers and reporters physically pushing into these spaces in the name of journalism—that Black queer and trans people in NYC have always guarded and loved and supported each other while surviving and dying by state and community violence.

Reports show that in 2023, at least 15 transgender and gender non-conforming people were killed in the United States; in 2022, 32 people; and 2021, 59.

In early July, Fernielle Mary Mora, a trans woman from the Bronx, was found dead in her home. Multiple threats were made against her life and reported to the police. The family still does not know what happened to her.

Weeks after Mary’s death, O’Shae was stabbed at the Mobil gas station on Coney Island Avenue and Avenue P.

Over 400 people showed up to the memorial ball, organized by groups like Black Trans Liberation, Destination Tomorrow, Ballroom We Care, House Lives Matter, and New Pride Agenda. Speakers included trans organizers Gia Love and Qween Jean.

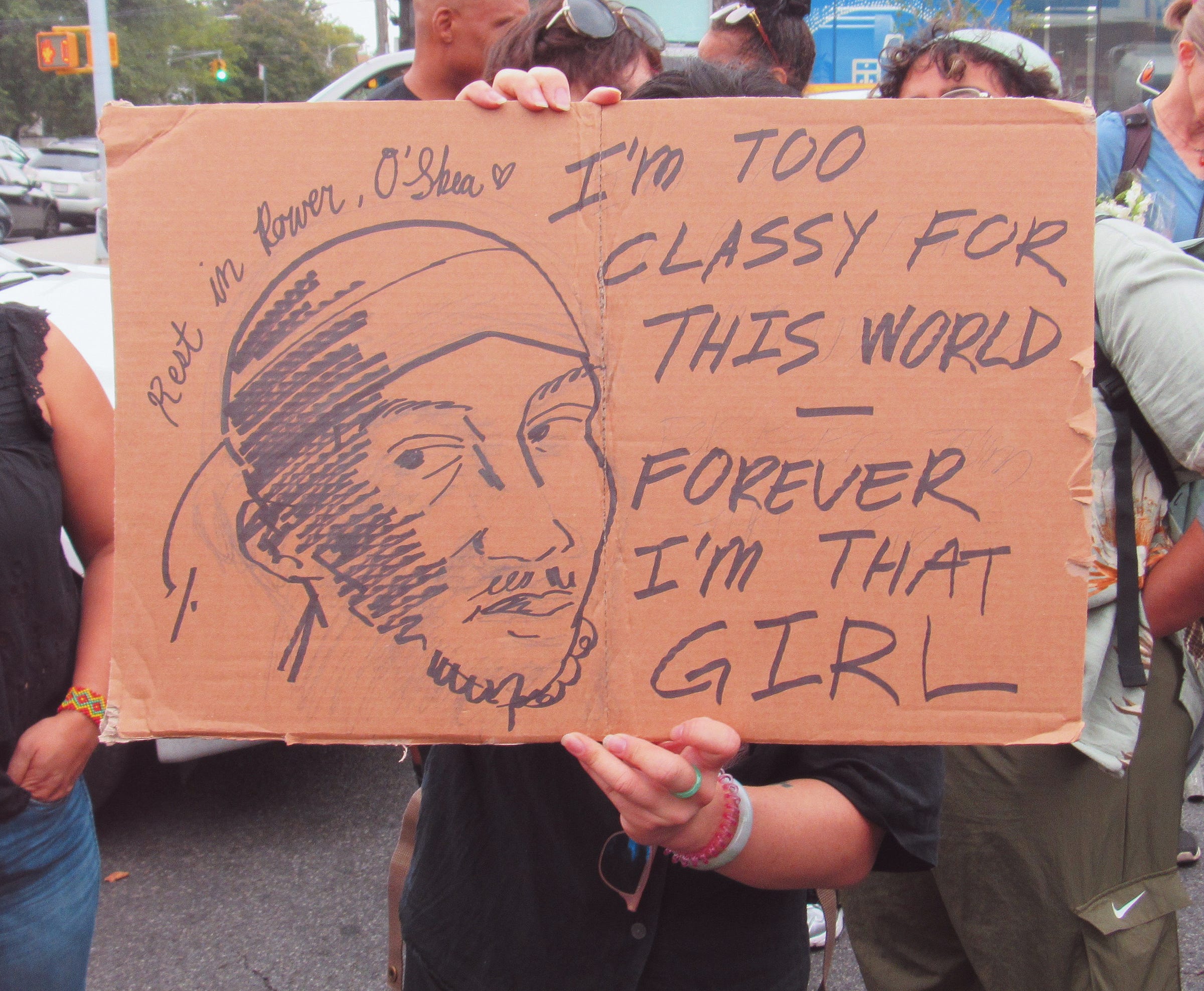

People brought flowers and signs.

People cried and hugged and vogued.

People played “Renaissance.”

There are moments of silence and prayer. A reverend prays. The crowd closes our eyes. Everyone is quiet, sad, together, loving.

Qween Jean speaks often throughout the memorial.

She is one of the organizers. She is a transgender community organizer and costume designer, She was born in Haiti, and is currently New York City-based.

Qween is one of the founders of Black Trans Liberation. Michael Love Michael, in an article for Vogue earlier this summer, writes, “Black Trans Liberation has two chief aims: encouraging food sovereignty among TGNC people and fostering a sense of shared responsibility within the larger LGBTQIA+ community.”

I learn about Qween Jean and the ball thanks to Siddika, who is also teaching me about Black and Brown queer and trans history and organizing in New York City. They invite me to consider queerness more fully and to apply this understanding to the stories I write.

Three months ago, Qween was arrested.

In Them, Samantha Riedel writes:

On May 31, following a “Trans Revolution” rally in Washington Square Park protesting anti-trans laws and violence across the U.S., police arrested Qween Jean, the legendary New York City activist who organized the rally, on charges of using a megaphone without a permit. According to local publication The Villager, Jean entered a nearby deli to evade capture, but police eventually cleared the area and arrested her.

The police surveil what she does, what this community does. Despite this, they gather and take up space.

Qween is moving, powerful, militant. Empowering. She describes how afraid people are of queer Black love, revolution. “We belong any and everywhere,” she stated.

This was my first time at a queer action. I stood with comrades toward the back of the vigil, directly in front of the police barricades. At one moment, the barricades are moved back because the crowd is asked to take steps back. Towards the front, people begin to crowd Qween Jean and other Black organizers and speakers sharing their thoughts on O’Shae and homophobic and transphobic violence.

The inner circle and spaces near Qween are not mine to occupy. I watch and stand from afar with other Bronx comrades. I photograph from where I stand. (For a closer, more intimate look at the memorial ball on Friday, and the following action on Saturday, check out the photographs taken by Bronx artist Shaira. The pictures they took are stunning.)

I capture signs and the backs of heads and flowers in people’s arms and hands. I take notes on what people say or chant around me.

One protestor describes how little New Yorkers actually know about the Black queer and trans community in NYC.

Another describes the violence they have witnessed against the community since the 1980s.

Organizers reminded the audience and Midwood community that their dancing and queerness were not illegal. That homophobic and transphobic rhetoric, both from the state and those in our own community, leads to violence.

I am deeply moved by the ball.

One of my favorite moments is when two cars stop next to the police barricades.

Five people step out and begin voguing. They pose and smile and fall to the ground. They are free and beautiful. They are cheered on until they are eventually stopped by an organizer. They state the police will use anything happening outside their perimeters as an excuse to stop the memorial.

O’Shae was loved deeply. People described their dancing ability and involvement in ballroom. People described their smile and how deeply they loved their people and community. People danced to remember O’Shae.

At various moments throughout the memorial, the crowd chants, again and again: O’Shae. O’Shae. O’Shae. O’Shae. O’Shae.

I am moved by how Black queer and trans New Yorkers mobilize and love and protect and honor and memorialize each other.

In awe of how powerful and revolutionary these spaces are forced to be while also dying at the hands of state and community violence. How they resist under empire, under our surveillance state. How they love and build.

“This is what Black queer love looks like,” Qween said.

After remembering the O’Shae memorial, I think about what it takes to galvanize hundreds of people in New York City. The vigil organizers spoke often about community safety.

What does it take to inspire people into action?

What does it take to communicate with one another after agreeing on how to support and love each other?

I think about how Black, immigrant communities can protect and house and feed one another, while also trying to ground community building in a Black, leftist, queer, trans vision for a better world.

How does local, community, borough-based organizing connect to the liberation those honoring and loving O’Shae called for this weekend?